How To Act Like A Jester

| Jester | |

|---|---|

| |

| Medium | Entertainer |

| Types | Court and theatre |

| Descendant arts | Harlequinade, comedian, clown |

| Originating era | 14th century–nowadays |

A jester, courtroom jester, fool or joker was a fellow member of the household of a nobleman or a monarch employed to entertain guests during the medieval and Renaissance eras. Jesters were also afoot performers who entertained common folk at fairs and town markets, and the discipline continues into the modern 24-hour interval, where jesters perform at historical-themed events.

During the Center Ages, jesters are often idea to accept worn brightly colored apparel and eccentric hats in a motley pattern. Their modernistic counterparts normally mimic this costume. Jesters entertained with a wide variety of skills: master amongst them were vocal, music, and storytelling, but many also employed acrobatics, juggling, telling jokes (such as puns, stereotypes, and fake), and performing magic tricks. Much of the entertainment was performed in a comic style. Many jesters made gimmicky jokes in discussion or song about people or events well known to their audiences.

Etymology [edit]

The modern use of the English language word jester did not come into use until the mid-16th century, during Tudor times.[1] This mod term derives from the older form gestour, or jestour, originally from Anglo-Norman (French) pregnant 'storyteller' or 'minstrel'. Other before terms included fol, disour, buffoon, and bourder. These terms described entertainers who differed in their skills and performances but who all shared many similarities in their role as comedic performers for their audiences.[1] [two] [3]

History [edit]

In ancient Rome, a similar tradition of professional jesters were called balatrones .[4] [ full commendation needed ] Balatrones were paid for their jests, and the tables of the wealthy were generally open to them for the sake of the amusement they afforded.[5]

Other cultures such as the Aztecs and the Chinese employed cultural equivalents to the jester.[6] [seven]

English royal courtroom jesters [edit]

Many royal courts throughout English language purple history employed entertainers and nigh had professional fools, sometimes called "licensed fools". Amusement included music, storytelling, and concrete comedy. Fool Societies, or groups of nomadic entertainers, were frequently hired to perform acrobatics and juggling.[8]

Jesters were also occasionally used every bit psychological warfare. Jesters would ride in front of their troops, provoke or mock the enemy, and even serve as messenger. They played an important part in raising their own army'southward spirits past singing songs and reciting stories.[9] [10]

Henry Eight of England employed a jester named Will Sommers. His daughter Mary was entertained by Jane Foole.[11]

During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I of England, William Shakespeare wrote his plays and performed with his theatre company the Lord Chamberlain's Men (later called the King's Men). Clowns and jesters were featured in Shakespeare'due south plays, and the visitor's expert on jesting was Robert Armin, author of the book Fooled upon Foole. In Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, Feste the jester is described as "wise enough to play the fool".[12]

In Scotland, Mary, Queen of Scots, had a jester chosen Nichola. Her son, Rex James VI of Scotland, employed a jester called Archibald Armstrong. During his lifetime Armstrong was given corking honors at court. He was eventually thrown out of the King'due south employment when he over-reached and insulted also many influential people. Fifty-fifty after his disgrace, books telling of his jests were sold in London streets. He held some influence at court yet in the reign of Charles I and estates of land in Ireland. Anne of Denmark had a Scottish jester called Tom Durie. Charles I later employed a jester called Jeffrey Hudson who was very popular and loyal. Jeffrey Hudson had the championship of "Majestic Dwarf" because he was curt of stature. I of his jests was to exist presented hidden in a giant pie from which he would leap out. Hudson fought on the Royalist side in the English language Civil War. A third jester associated with Charles I was called Muckle John.[xiii]

Jester'southward privilege [edit]

Jester's privilege is the ability and right of a jester to talk and mock freely without being punished. As an acknowledgement of this right, the court jester had symbols denoting their condition and protection under the law: the crown (cap and bells) and scepter (marotte), mirroring the royal crown and scepter wielded by a monarch.[14] [15]

Martin Luther used jest in many of his criticisms against the Catholic Church.[sixteen] In the introduction to his To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, he calls himself a court jester, and, later on in the text, he explicitly invokes the jester's privilege when saying that monks should break their guiltlessness vows.[16]

Natural vs artificial fools [edit]

In that location are two major groups when information technology comes to defining fools: bogus fools and natural fools. Natural fools consisted of people who were deemed "mentally defective," or as having a "deficiency in their teaching, experience or innate capacity for understanding," and stood as someone for the balance of society to laugh at.[17] [ full citation needed ] This policy was not generally criticized during its time. Groups of people even saw this human action every bit a positive one, as these "natural" comedians were not typically able to have a job or earn any sort of living on their ain. The second group, artificial fools, is what virtually people in modern times imagine when they hear the give-and-take "jester": someone who comes up with witty and original jokes in order to entertain a imperial court. The master divergence between the 2 groups is that a natural fool's comedy is not done intentionally while an artificial fool's is.

Political significance [edit]

Scholar David Carlyon has cast incertitude on the "daring political jester", calling historical tales "counterfeit", and last that "popular civilisation embraces a sentimental image of the clown; writers reproduce that sentimentality in the jester, and academics in the Trickster", but it "falters as analysis".[18]

Jesters could also requite bad news to the King that no one else would dare evangelize. In 1340, when the French armada was destroyed at the Boxing of Sluys by the English, Phillippe Half-dozen's jester told him the English sailors "don't even have the guts to jump into the water similar our brave French".[seven]

Cease of tradition [edit]

After the Restoration, Charles Two did not reinstate the tradition of the court jester, just he did greatly patronize the theatre and proto-music hall entertainments, especially favouring the work of Thomas Killigrew. Though Killigrew was not officially a jester, Samuel Pepys in his famous diary does call Killigrew "The Rex's fool and jester, with the power to mock and revile even the most prominent without penalty" (12 February 1668). The last British nobles to keep jesters were the Queen Female parent's family, the Bowes-Lyons.

In the 18th century, jesters had died out except in Russia, Espana, and Germany. In France and Italy, travelling groups of jesters performed plays featuring stylized characters in a course of theatre chosen the commedia dell'arte. A version of this passed into British folk tradition in the form of a puppet testify, Dial and Judy. In France the tradition of the court jester ended with the French Revolution.

In the 21st century, the jester has been revived and tin can still be seen at medieval-manner fairs and pageants.

In 2015, the town of Conwy in Northward Wales appointed Russel Erwood (aka Erwyd le Fol) every bit the official resident jester of the town and its people, a postal service that had been vacant since 1295.[19] [20]

Other countries [edit]

Poland's most famous court jester was Stańczyk, whose jokes were unremarkably related to political matters, and who later became a historical symbol for Poles.[21] [22]

In 2004 English Heritage appointed Nigel Roder ("Kester the Jester") equally the State Jester for England, the first since Muckle John 355 years previously.[23] However, following an objection by the National Society of Jesters, English Heritage accepted they were not authorised to grant such a championship.[24] Roder was succeeded every bit "Heritage Jester" by Pete Cooper ("Peterkin the Fool").[25]

In Germany, Till Eulenspiegel is a folkloric hero dating back to medieval times and ruling each year over Fasching or Carnival time, mocking politicians and public figures of power and authorization with political satire like a mod-twenty-four hours court jester. He holds a mirror to brand us aware of our times (Zeitgeist), and his sceptre, his "bauble," or marotte, is the symbol of his power.

In 17th century Spain, niggling people, frequently with deformities, were employed as buffoons to entertain the king and his family, especially the children. In Velázquez's painting Las Meninas two dwarfs are included: Maria Bárbola, a female person dwarf from Germany with hydrocephalus, and Nicolasito Portusato from Italy. Mari Bárbola can also be seen in a later on portrait of princess Margarita Teresa in mourning past Juan Bautista Martinez del Mazo. There are other paintings by Velázquez that include court dwarves such as Prince Balthasar Charles With a Dwarf.

During the Renaissance Papacy, the Papal courtroom in Rome had a court jester, similar to the secular courts of the time. Pope Pius V dismissed the court Jester, and no later Pope employed one.

In Japan from the 13th to 18th centuries, the taikomochi, a kind of male geisha, attended the feudal lords (daimyōs). They entertained generally through dancing and storytelling, and were at times counted on for strategic advice. By the 16th century they fought alongside their lord in battle in improver to their other duties.

Tonga was the first royal court to appoint a court jester in the 20th century; Taufa'ahau Tupou IV, the King of Tonga, appointed JD Bogdanoff to that role in 1999.[26] Bogdanoff was afterwards embroiled in a financial scandal.[27]

As a symbol [edit]

The root of the word "fool" is from the Latin follis, which means "bag of air current" or bellows or that which contains air or breath.[28]

In Tarot [edit]

In Tarot, "The Fool" is a carte du jour of the Major Arcana. The tarot depiction of the Fool includes a man (or less oft, a woman) holding a white rose in one manus and a small-scale bundle of possessions in the other with a canis familiaris or true cat at his heels. The fool is in the act of unknowingly walking off the edge of a cliff, precipice, or other high place. (Compare: Joker (playing carte)).

In literature [edit]

In literature, the jester is symbolic of mutual sense and of honesty, notably in King Lear, where the court jester is a grapheme used for insight and communication on the part of the monarch, taking reward of his license to mock and speak freely to dispense frank observations and highlight the folly of his monarch. This presents a ambivalent irony as a greater human being could dispense the same advice and detect himself being detained in the dungeons or even executed. Only equally the lowliest member of the court can the jester be the monarch's nearly useful adviser.

In Shakespeare [edit]

The Shakespearean fool is a recurring character type in the works of William Shakespeare. Shakespearean fools are usually clever peasants or commoners that use their wits to outdo people of higher social standing. In this sense, they are very similar to the existent fools, and jesters of the time, but their characteristics are profoundly heightened for theatrical effect.[29] The "groundlings" (theatre-goers who were as well poor to pay for seats and thus stood on the 'ground' in the front past the phase) that frequented the World Theatre were more than likely to be fatigued to these Shakespearean fools. However they were as well favoured past the nobility. Most notably, Queen Elizabeth I was a great admirer of the pop actor who portrayed fools, Richard Tarlton. For Shakespeare himself, however, histrion Robert Armin may have proved vital to the cultivation of the fool character in his many plays.[30]

Mod usage [edit]

Buffoon [edit]

In a like vein, a buffoon is someone who provides entertainment through inappropriate appearance or behavior. Originally the term was used to describe a ridiculous only amusing person. The term is now frequently used in a derogatory sense to draw someone considered foolish, or someone displaying inappropriately vulgar, bumbling or ridiculous behavior which is a source of full general amusement. The term originates from the former Italian "buffare", meaning to puff out one's cheeks[31] that besides applies to bouffon. Having swelled their cheeks they would slap them to expel the air and produce a dissonance which amused the spectators.[32]

Carnival and medieval reenactment [edit]

Today, the jester is portrayed in different formats of medieval reenactment, Renaissance fairs, and amusement, including flick, stage operation, and carnivals. During the Burgundian and the Rhenish funfair, cabaret performances in local dialect are held. In Brabant this person is called a "tonpraoter" or "sauwelaar", and is actually in or on a barrel. In Limburg they are named "buuttereedner" or "buutteredner" and in Zeeland they are chosen an "ouwoer". They all perform a cabaret speech in dialect, during which many current bug are reviewed. Frequently there are local situations and celebrities from local and regional politics who are mocked, ridiculed and insulted. The "Tonpraoter" or "Buuttereedner" may exist considered successors of the jesters.[33]

Notable jesters [edit]

Historical [edit]

- Tom le Fol (c. 13th century), the 1st resident jester of Conwy, North Wales, and personal jester to Edward I

- Triboulet (1479–1536), court jester of Kings Louis XII and Francis I of France

- Stańczyk (c. 1480–1560), Polish jester

- João de Sá Panasco (fl. 1524–1567), African courtroom jester of Rex John III of Portugal, eventually elevated to admirer courtier of the Majestic Household and Knight of St. James

- Jane Foole (c. 1543 - 1558), Court Jester of Catherine Parr and Mary I of England

- Volition Sommers (died 1560), court jester of King Henry VIII of England

- Chicot (c. 1540–1591), courtroom jester of King Henry III of France

- Mathurine de Vallois (fl. 1589 - fl. 1627), court jester of Henry Iii of France and Henry Four of France

- Archibald Armstrong (died 1672), jester of Rex James I of England

- Jeffrey Hudson (1619–c. 1682), "court dwarf" of Henrietta Maria of French republic

- Jamie Fleeman (1713–1778), the Laird of Udny'south Fool

- Perkeo of Heidelberg, 18th century, jester of Prince Charles III Philip, Elector Palatine

- Sebastian de Morra, (died 1649) court dwarf and jester to Male monarch Philip 4 of Spain

- Don Diego de Acedo, court dwarf and jester to Philip IV of Spain

- Roulandus le Fartere, a medieval flatulist who lived in twelfth-century England

Modern-day jesters [edit]

- Jesse Bogdonoff (b. 1955), court jester and financial advisor to Male monarch Taufa'ahau Tupou IV of Tonga[ commendation needed ]

- Russel Erwood (b. 1981), known as Erwyd le Fol, is the 2nd official resident jester of Conwy in N Wales replacing the jester of 1295[34] [35]

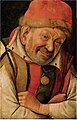

Gallery [edit]

-

John Dawson Watson - Friends in Quango

-

Queen Henrietta Maria with Sir Jeffrey Hudson by Van Dyck

-

Portrait of the Ferrara Court Jester Gonella by Jean Fouquet 1445

-

Masquerade by Golovin - Jester with hunch (1917, Bakhrushin museum)

-

Portrait of the Jester Balakirev (1699-1763)

-

The Court Jester of Tabbyland

-

Шут. Фрагмент миниатюры "Gaharié recevant le chapel" из "Романа о Ланселоте" (Français 112 (1), fol. 45), ок. 1470

-

Jester-doll made past Olina Ventsel (1938-2007)

-

![Illustration p. 284 from "Queen of the Jesters" [Caption: Brought it down with a Crash upon the Head of Henri de Villefort.] Illustrator unknown; text by Max Pemberton.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/QueenOfTheJesters_284--with_a_crash_upon_the_head_of_de_Villefort.jpg/93px-QueenOfTheJesters_284--with_a_crash_upon_the_head_of_de_Villefort.jpg)

Illustration p. 284 from "Queen of the Jesters" [Caption: Brought it down with a Crash upon the Caput of Henri de Villefort.] Illustrator unknown; text by Max Pemberton.

-

Venne Woman and a jester

-

Man dressed as a jester, with a fool's cap, motley and white tights.

-

Statue of a jester depicted in the book Letters from England by Karel Čapek

-

Oil on panel, signed with monogram, bears inscribed label for the Dundee Fine art Exhibition, 1877, fastened opt the reverse, 23.7x15.five cm.

-

Private collection, oil on canvas. Jacob Jordaens (1641-1645).

-

Jester Resting on a chair by William Merritt Chase, 1875, the work is one of several trial poses William Merritt Chase painted as preparation for his Keying Up- The Court Jester

-

P. B. Abery (1877?-1948) & Wallace Jones

-

The Court Jester by John Watson Nicol, 1895, oil on canvass, 41 ten 57 cm. (16.1 10 22.4 in.)

-

Rahere, Bouffon de Henry I et de la Reine Matilda, début 1100.

-

Chase William Merrit

-

-

Caricature of a court jester of Philip the Adept, duke of Burgundy, in the 16th century Recueil d'Arras, a collection of portraits copied by Jacques de Boucq

-

William Burges, English builder

-

Cocky Portrait in a Jester'due south Costume

-

Royal Jester Stańczyk

-

Jester Knight Christoph by Hans Wertinger (1515, Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid)

-

Akram Mutlak Ménage À Trois Öl auf Leinwand

-

Bouffon

-

A jester with ass'southward ears

See too [edit]

- Basil Fool for Christ

- Cap 'northward' Bells

- Clowns

- Clown society

- Drollery

- Fool (stock graphic symbol)

- Fool's literature

- Foolishness for Christ

- Fools Social club, California "Jester" themed amusement troupe

- Harlequin

- Afoot poet

- Jester of Genocide

- King Momo

- Madame d'Or

- Marotte – the staff ofttimes carried by jesters

- Master of the Revels

- Punakawan, comedic sidekick in Javanese tales

- Skomorokh

- Trickster

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ a b Soutworth, John (1998). Fools and Jesters at the English Court. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. pp. 89–93. ISBN0-7509-1773-3.

- ^ Welsford, Enid (1935). The Fool: His Social & Literary History. London: Faber & Faber. pp. 114–115.

- ^ "Jester". Online Etymology Dictionary . Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Horace Sat. i. ii. 2. (cited by Allen)

- ^ Notes and Queries: A Medium of Inter-Communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, Etc. Bell. 1868.

- ^ "Jester". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved 2012-06-07 .

- ^ a b Otto, Beatrice (2001). Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing. ISBN978-0226640914.

- ^ Kelly, Debra (2020-12-26). "What It Was Really Like To Exist A Court Jester - Grunge". Grunge.com . Retrieved 2022-x-sixteen .

- ^ sheldon, Natasha (2018-09-19). "The Part of Fool was a Staple in Medieval Culture... In Some of the Most Unexpected Ways". History Drove . Retrieved 2022-ten-16 .

- ^ Kelly, Debra (2020-12-26). "What It Was Really Like To Be A Court Jester - Grunge". Grunge.com . Retrieved 2022-10-16 .

- ^ Westfahl, Gary (2015-04-21). A Day in a Working Life: 300 Trades and Professions through History [3 volumes]: 300 Trades and Professions through History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN978-i-61069-403-2.

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1906). The Works of Shakespeare ....: Twelfth night; or, What yous will, ed. by M. Luce. Methuen & Company Limited.

- ^ Buckle, Henry Thomas (1872). The Miscellaneous and Posthumous Works of Henry Thomas Buckle. Longmans, Green and Company.

- ^ "Medieval Jesters – And their Parallels in Modern America". History is At present Magazine, Podcasts, Blog and Books | Modernistic International and American history . Retrieved 2022-02-18 .

- ^ Billington, Sandra. "A Social History of the Fool", The Harvester Press, 1984. ISBN 0-7108-0610-viii

- ^ a b Hub Zwart (1996), Ethical consensus and the truth of laughter: the construction of moral transformations, Morality and the meaning of life, vol. 4, Peeters Publishers, p. 156, ISBN9789039004128

- ^ Swain 1–2

- ^ Carlyon, D. (2002). "The Trickster as Bookish Comfort Nutrient". The Periodical of American Culture. 25 (i–2): xiv–18. doi:10.1111/1542-734X.00003.

- ^ "Welsh boondocks appoints first official jester in 700 years". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on 2018-10-eleven. Retrieved 2016-10-14 .

- ^ Day, Liz (2015-08-08). "This official town jester can balance a flaming barbecue on his caput..!". walesonline . Retrieved 2016-10-14 .

- ^ Janusz Pelc; Paulina Buchwald-Pelcowa; Barbara Otwinowska (1989). Jan Kochanowski 1584-1984: epoka, twórczość, recepcja (in Polish). Lublin: Instytut Badań Literackich, Polska Akademia Nauk. Wydawnictwo Lubelskie. pp. 425–438. ISBN978-83-222-0473-three.

- ^ Jan Zygmunt Jakubowski, ed. (1959). "Przegląd humanistyczny" (in Polish). three. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: 200.

- ^ "Jesters joust for historic office". BBC News. 2004-08-08. Retrieved 2010-05-06 .

- ^ Griffiths, Emma (2004-12-23). "England | Jesters go serious in name row". BBC News . Retrieved 2012-07-11 .

- ^ "England | Jester completes 100-mile tribute". BBC News. 2006-08-09. Retrieved 2012-07-11 .

- ^ "Tonga royal decree appointing JD Bogdanoff as court jester". Archived from the original (JPEG) on 2012-xi-06. Retrieved 2009-10-29 .

- ^ "Tongan court jester faces trial". BBC News. 11 Baronial 2003. Retrieved 2009-10-29 .

- ^ "Online Etymology Lexicon". www.etymonline.com . Retrieved 2017-03-30 .

- ^ Warde, Frederick B. (1913). The fools of Shakespeare: an ... - Frederick B. Warde - Google Boeken . Retrieved 2011-12-24 .

- ^ "History of the Fool". Foolsforhire.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2011-12-24 .

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica; or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature, Volume iv. Archibald Constable and Company. 1823. p. 780.

- ^ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge Vol.III, London (1847), Charles Knight, p.918

- ^ Dwelling Kalender Nieuws Zoekertjes Albums Copyright. "Wat is carnaval? | Fen Vlaanderen". Fenvlaanderen.be. Retrieved 2014-01-23 .

- ^ "Conwy jester to take new chore 'seriously'". BBC News. 2015-07-sixteen. Retrieved 2016-10-14 .

- ^ "Bristol juggler to become North Wales town's first official jester in 700 years". Bristol Post. 2015-07-xix. Archived from the original on 2015-08-xviii. Retrieved 2016-ten-14 .

References [edit]

- Billington, Sandra A Social History of the Fool, The Harvester Press, 1984. ISBN 0-7108-0610-8

- Doran, John A History of Court Fools, 1858

- Hyers, G. Conrad, The Spirituality of Comedy: comic heroism in a tragic world 1996 Transaction Publishers ISBN 1-56000-218-2

- Otto, Beatrice M., "Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World," Chicago University Press, 2001

- Southworth, John, Fools and Jesters at the English language Courtroom, Sutton Publishing, 1998. ISBN 0-7509-1773-3

- Swain, Barbara. "Fools and Folly During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance" Columbia Academy Press, 1932.

- Welsford, Enid: The Fool : His Social and Literary History (out of print) (1935 + subsequent reprints): ISBN 1-299-14274-five

- Janik, Vicki K. (ed.) (1998). Fools and Jesters in Literature, Art, and History: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group, United states of america. ISBN 0313297851.

External links [edit]

![]()

Wikimedia Eatables has media related to Jesters.

![]()

- Fooling Around the World (A history of the court jester)

- Foolish Clothing: Depictions of Jesters and Fools in the Heart Ages and Renaissance What 14th-16th century jesters wore and carried, every bit seen in illustrations and museum collections.

- Costume (Jester Hat), ca. 1890-1920, in the Staten Island Historical Lodge Online Collection Database

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jester

0 Response to "How To Act Like A Jester"

Post a Comment